.jpg)

Crocodile Men

With their unique clan scarification running down their backs (and fronts) into their trousers, the crocodile men of the Middle Sepik in Papua New Guinea can often be found inside the spirit house: carving, drumming, telling stories; or just sitting chatting and smoking or chewing betel nut.

What is “culture”?

That was the question for our first assigned essay in “Culture Myth and Symbolism”, an upper-level anthropology course I took at university, many, many years ago. Deceptively simple, the “answer” – if there is one – became increasingly layered and complex the more I delved into tomes written by the notable ‘modern’ anthropologists of the 20th century. As the course outline puts it:

It is one thing to witness the artefacts of culture; quite another thing to understand them. Another essay I researched at the time was about body art and adornment: because clothing, makeup, tattooing, scarification, and even posture, can tell us something about the culture we embody.

Memories of this course – one of my favourites during my university days – came back to me when I was in Papua New Guinea last year. This was especially true in the Middle Sepik region, where initiated men in the Crocodile Clan embody the crocodile: their totem and symbol of strength and power. They believe that humans are the offspring of migrating ancestral crocodiles; their initiation ceremony (for males only!) takes boys and moves them through androgyny and into manhood – albeit with a crocodile spirit.

Men of the crocodile clan are heavily scarified to look like the reptiles they epitomise. Circles of scar tissue surrounding their nipples mimic crocodile eyes; nostrils are carved near the abdomen. Their backs are scarred in the form of the powerful animal’s rear legs and tail.

American anthropologist Nancy Sullivan, who lived and worked in Papua New Guinea for many years, was present during a crocodile-clan initiation ceremony. The young men were taken, under the protection of their mothers’ brothers, to the haus tambaran (spirit house), where hundreds of cuts were incised: symbolically bleeding out their mothers’ postpartum blood to make them ‘men’ of their father’s lineage. Tigaso tree oil and clay were applied to the open wounds. Then the boys lay down by a smoky fire to infect the wounds so that keloid scar tissue was produced. During the whole process, flutes and hour-glass shaped kundu drums played to ‘confuse the women’.

Other sources talk about the two months that the young men are sequestered in the spirit houses, learning their clan genealogies, the significance of every clan song and ceremony, and the origins and spiritual purpose of every image or object in the haus tambaran. (For a much more detailed – and somewhat graphic – account of the whole process, have a look at the fascinating article by ‘tattoo anthropologist’ Lars Krutak.)

I was in the village of Kanganaman in the Middle Sepik with photographer Karl Grobl from Jim Cline Photo Tours, not for an initiation (which only happens every two or more years) but for the much more enjoyable experience of watching a sing-sing – a festival of culture, dance and music by a gathering of tribes, villages or clans (more about that soon).

Clan culture is strong here: crocodiles (pukpuk) are not the only clan spirits or totems. Eagles (taragau), snakes, cassowary (muruk), pigs, birds of paradise, and other animals, can each represent a spirit clan, and each village usually has several clans and sub-clans. The inter-relationship of these totems is complex, and although one man tried to explain his attachments (separately through his mother and his father) to two spirit symbols, I can’t begin to understand how it all works. It is said, however, that the more diverse clans and spirits a village has, the stronger the village will be – especially in protecting against black magic. Sorcery still looms large in the regional psyche.

The people along the Sepik River had almost no contact with Westerners until the 19th century, and the region is still relatively remote and difficult to access (see: Welcome to the Spirit House!). Life here has changed little here for thousands of years. There is no electricity (except by generator for the few hardy tourists) and no running water. What there is is unremitting heat that envelopes one like a wet blanket, and the constant buzz of insects – including hordes of mosquitos, which may or may not be carrying malaria, dengue fever, or Japanese encephalitis.

No wonder the locals almost all chew the ubiquitous betal (areca) nut!

Still, I would do it again. It was still fascinating to meet the crocodile men, to listen to their stories, and to see some of their extraordinary body markings.

.jpg)

Kanganaman Village House

The village we stayed in is a modest place. Most of the houses are like this one: simple rooms with bamboo floors, and woven walls and roof, raised up on stilts to protect against river floods.

.jpg)

Kids at a Tree

Kanganaman Village is small, but PNG has a young population (more than 33% are under 14 years old), so it is no surprise that there are plenty of children to hang around and watch us every time we go anywhere.

Kids in the Green

Inside the Spirit House

The Kanganaman spirit house is lofty and large. Local women (and young men who are not initiated) are not allowed inside, but we are permitted – as long as we take our hats off and don’t touch anything without checking. Many of the objects – including the wicker cone-shaped tumbuan dance costumes on the left, are sacred.

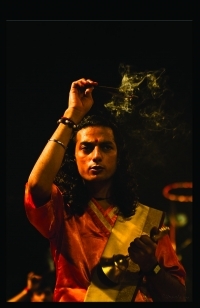

Drummer

Inside the haus tambaran – the spirit house – the village elders set up drum rhythms. Garamut (slit drums) like this one, are carved from a tree trunk, and engraved and painted in stages. They are kept in the men’s spirit houses and pounded with poles during special ceremonies.

Crocodile Man’s Shoulder

When the men take a break from their drumming, they sit on the bench that runs along one side inside the spirit house.

Crocodile Men

The patterns of scarification are all somewhat different – depending on the cutter who has done them and the design within the father’s family. But, they are all impressive!

Smiling Drummer

Smiling Crocodile Man

You can just barely see the scarification on this man’s chest.

Crocodile Man’s Back

The men are all quite happy to pose briefly for us.

Decorated Crocodile Skull

Like all the art and artefacts inside the spirit house, this crocodile skull has significance: we were told very clearly not to touch it. Shells are central to PNG culture, and were once used as currency. So, this skull has monetary worth as well as artistic and spiritual value.

Crocodile Elder

The Eagle, the Fish and the Woman

All of the wonderful carvings in the spirit house have a story – some of which their creators gladly explain to us.

Crocodile

The crocodile motif shows up in various forms.

Drums, Painted Masks, Story Carvings and Stools

Even objects that have inhabited been by spirits get replaced and recycled – so many of the colourful objects in the spirit house can be purchased. The whole Sepik region is very popular with collectors of artefacts.

Cassowary Eyes?

Soon it is time for the men of the village we are staying in to apply their face paint for the sing-sing their are hosting.

Face Painting

The face painting is a long, delicate process, but because the designs follow a prescribed village pattern, the men can take turns working in the stifling spirit-house heat.

Crocodile Man Dancing

The dancers at the sing-sing illustrate that idea of villages having representatives of different clans: …

“Wild Duck”

… each village comes with its own ancestral story-dance and their unique face-paint representing their spirit totem.

Crocodile Man in a Shell Pectoral Adornment

While each village has a ‘set’ costume, the men add on their own personal touches. This old kina shell pectoral adornment is very valuable and has probably been passed down for generations.

Firelight on the Scars

When the dancers from neighbouring villages have all gone home, we gather in the spirit house …

Firelight on the Sacred Carvings

… where the light from the fire turns the spirit-infused carvings quite atmospheric!

It truly is a different world and a foreign – but fascinating – culture.

Until next time,

.png)

.png)

[…] getting their face-paint ready for their dance performance (see: A Black and White View and Crocodile Men). But, Kanganaman has not one, but two spirit houses (see: Welcome to the Spirit House). The […]

[…] stay in the little village of Kanganaman in the Middle Sepik (see: Welcome to the Spirit House and Crocodile Men), most of us were looking forward to our boutique accommodation in Wewak, with hot showers in the […]

[…] village nearby. Each village in the Sepik region has several clans and sub-clans (see: Crocodile Men), with complex inter-relationships of the corresponding totems. It is said that the more diverse […]